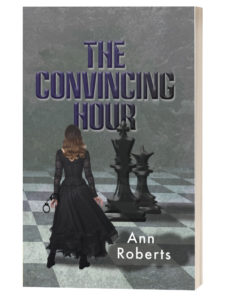

The Convincing Hour

Juvenile delinquents are vanishing from Lakeview, Michigan. Story Black, a brilliant fifteen-year-old, has heard the smartest kids go from jail to a special school—and then college. The mastermind behind it all is Lakeview’s newest citizen, Charlotte “Char” Barnaby, a former high school principal and winner of the largest lottery jackpot in history. She brings her powerful billions back to her dying hometown, determined to save it and the worthiest children—regardless of what it costs.

Story plans to be next. Getting arrested is easy but getting out of Lakeview may be impossible. Standing between her and her new life is her mother, Patty Black, a meth user with a genius I.Q. and a mysterious past of her own. Char launches an elaborate scheme to convince Patty to let Story go, but Patty is an immovable force, unwilling to put Story’s happiness before her own. If Story wants the future she sees, she must confront her mother and be willing to lose everything, even their relationship.

Several years ago during my tenure as an educational consultant, I was sitting in a classroom watching an excellent teacher engage every student in her room. They volunteered answers, respectfully commented on each other’s opinions and seemed genuinely thrilled about learning. No one acted out and no one refused to do what the teacher asked. It was the dream lesson teachers strive to achieve every day they teach. It was the ideal classroom.

Then I remembered where I was sitting: juvenile detention.

I scanned the room, noticing the gray sweatpants, various-colored T-shirts, and the slip-on Vans. No one held a pencil longer than three inches since it could be used as a weapon. Many had tattoos creeping up their respective necks or down past their wrists. When it was time to do their independent work, they focused on their computers while two correction officers strolled down the aisles.

I knew each child had a heartbreaking story and to be sentenced to detention meant the kid had done something horrible or couldn’t stop committing a minor infraction and detention was the last resort. Yes, these were the bad kids but they sure didn’t act like it. What was different? As a school principal, I knew kids like this—in fact, I saw one there that had been at my school. They were constantly in trouble and consumed dozens of hours in finding services, working with the courts, supporting the families, and working with the police. Still, very little improved.

When I asked the detention principal, Frank Burnsed, why these habitually unsuccessful students were suddenly finding success and planning for a bright future, he explained that once the temptations were removed, as well as poor role models and a culture of the streets, many of the kids thrived. We spoke about life after jail and he shook his head. While some of the students would never see the inside of a cell again, many would return and a decent percentage would face prison. A lot of the kids hated the idea of leaving detention because they knew what waited for them.

I thought about those kids and what it would take to change the trajectory of their lives so they could thrive and be successful. It would take a lot of money, changing a lot of laws that keep the poor and minorities down, dispelling some long-held notions about “family,” and admitting that for many of our kids, the current educational system is broken.

The Convincing Hour is both a love letter to all of my students and an answer to the question I asked myself. Story Black is a survivalist, taking care of herself and her genius-I.Q. mother, Patty, a meth addict. Story wants something better for herself and she realizes that road leads through the local juvenile detention facility to a school designed by Charlotte Barnaby, a former principal who wins the largest lottery ever. The only person standing between Story and her future is Patty.

Can Story stand up to Patty and rewrite her predictable future?

Chapter Four

“What’s your name?”

“Story. Story Black.”

“How old are you?”

“Fifteen. Sixteen in a month.”

“And why are you in jail?”

“I held up a convenience store with another girl.”

“Did you know she had a knife?”

“No,” I lied.

The woman interviewing me called herself Margaret, but I knew that wasn’t her real name. She’d looked slightly to the right when she introduced herself, like she was scrolling through her contacts, picking a name just for this interview. She glanced at an open folder in front of her, confirming what I said was true. While she debated her next question, I listened to the muffled kabooms of the hallway door clanging shut every time someone entered or exited the visitor’s area of juvenile detention. I re-crossed my legs and accidentally kicked one of the table’s plastic legs.

“Sorry,” I said quickly.

“No worries,” Margaret replied without looking up from her notes. “First time offender. Decent grades in school, although teachers say you could do better. It says your probation officer is Charity Aguilera.” She paused and added, “Great name for a P.O.”

“Yeah. She always makes fun of her name.”

Margaret scanned the P.O. log that Charity filled out when we met each week. “Says you’re doing great.”

I nodded and my knee bumped the table leg again. “Again, sorry.”

Margaret looked up and smiled warmly. “It’s okay. Take a deep breath. These rooms are the size of a shoebox.”

She wasn’t kidding. The tiny interview room was barely big enough for two people, and we had three counting the videographer, plus a camera on a tripod. I pictured myself frozen so I’d stop flailing around like a baby. Wilkey, a kid who’d been interviewed a few weeks before, told me to chill while I waited for each question. He thought his nervousness fucked up his chances.

Margaret’s brown eyes sucked me in. “What’s the worst part about being in jail, Story?”

“The little pencils,” I said automatically.

“Why?”

I sat up straight. “They’re symbols, like symbols in literature. Outside in regular schools nobody ever keeps a short pencil. You throw it out and get a new one from the teacher. But in here it’s the best we’ll get and it’s really hard to write with a tiny pencil. My hand starts to cramp. And I like to write. Sometimes I think about the teachers sitting at home, breaking perfectly good pencils in half while they watch their favorite shows. Then before they go to bed, they sharpen them down to practically nothing. Such a waste.”

“You understand why the detention teachers only supply short pencils, right? It’s a safety issue.”

“I get it. Nobody’s gonna shank somebody with a tiny stub.”

Her eyes narrowed as if she were studying a speck. “Why do you do that?”

“Do what?”

“You talk about literary symbols like a college professor and then you revert to colloquial street language. Why?”

I couldn’t hide my surprise. “Well,” I mumbled, “I’ve realized there’s a way to act in here. A way to talk so you don’t sound stuck up and people don’t give you shit. That’s really how it is in life.” I shrugged. “I don’t know.”

When I looked up, she was staring at me. “That’s not true. We’ve been watching you, Story. There isn’t much you don’t know.”

She smiled and I felt a tug at the corners of my mouth. She was pretty. Her skin was much darker than mine, and she had soft brown eyes and raven-colored hair. She was tall, so tall she had to sit sideways because her legs wouldn’t fit under the cheap plastic table with the high heels she wore. The red leather pumps matched the silk blouse underneath her black suit. She probably ate at trendy restaurants and sipped champagne with a group of female friends who possessed equally fabulous smiles.

The thought of beautiful women made me tingle. I liked girls. It was part of the reason I was in jail.

Her stylus flew across the face of her tablet as she took notes—notes about me. I wanted to say something unique to her, something that would make me stand out so she’d remember me.

Nobody is memorable in jail. That’s the point. Everybody wears the same blue drawstring pants and Vans rip-off slippers. The T-shirts are different colors depending on your behavior. I wore red and that meant I'd never gotten a strike from a Corrections Officer, a CO. I knew Margaret talked to a lot of kids and I imagined they rolled into one crazy juvenile delinquent with a really sad wardrobe.

I glanced at the camera in the corner. Like the blinking green light, I needed to be ON. My hands sweated and I rubbed them on my thighs while I waited for the next question. My leg bounced nervously and I pressed my heels to the floor to stop it. I didn’t want to bump the table again.

Margaret looked over her shoulder at the videographer crammed in the corner playing with her phone. She was Margaret’s opposite—short, blond and white. Her hair flipped to one side and scrambled in a few directions from the product she’d applied. She wore a T-shirt underneath an old corduroy jacket with leather patches on the elbows, and the cuffs of her jeans were tucked into sleek black boots. Sleek was definitely the right word for her.

She’d arrived first and stuck a microphone on my T-shirt to test it. “Are you nervous?” she’d asked.

“Yeah,” I admitted. “What kind of questions will she ask me?”

She leaned closer and glanced around the room, as if she was about to betray a secret. Then she said, “You’ll be asked to recite the Declaration of Independence.”

My eyes bugged out. “Seriously?”

She laughed and shook her head.

I let out a deep breath and laughed with her. “I’m glad you’re kidding. I know it’s an important document to the founding of our country, but I couldn’t recite it.” I noticed a copy of George Eliot’s Middlemarch sticking out of her camera bag. “I really liked that book,” I offered. I figured it couldn’t hurt to be pleasant with her. Maybe she’d put in a good word for me.

“What other books have you read?”

“Everything by Jane Austen. And I love Kurt Vonnegut and Willa Cather—and Mary Oliver. Just lots of people.” I didn’t want to name the hundreds of authors I’d read and sound stuck up.

She smiled and said, “All great ones. Just be yourself. I’m Jill.” We made small talk until Margaret arrived. Then Jill snuck behind the camera and turned it on. I stared at the light and willed myself to stop being nervous.

Margaret set her tablet down and leaned back. “You have an interesting name. How’d you get it?”

“It’s a long story.”

She chuckled. “I’d like to hear it.”

“It really would take too long to explain. I shouldn’t have been born. What happened made the local newspapers and my mother still carries the clipping from the paper around. So, I’m a story.”

I’d never told anybody that much, but Wilkey said I needed to impress this lady if I wanted anything to happen. He called her the key to getting out—out of jail and out of Lakeview, Michigan. Ms. Sutton had told me to be honest and respectful. I was trying.

“Tell me about your family.”

“I live with my mom now.”

“Any brothers and sisters?”

“Nope. I lived with my grandma, but she died two years ago and I went back to my mom.”

“Is your father in the picture?”

I shook my head. She didn’t write down my answer, so I could tell she already knew. “It’s just me and Mom now that Gran’s dead.”

She glanced at the folder. “Her name was Matilda Black, right?”

“Yes.”

“And your mother is Patience.”

“Yes, but she goes by Patty. Patience doesn’t really fit her.” I tried not to make it sound sarcastic but I snorted at the end of the comment.

She grinned but kept her eyes glued to the tablet. I waited for her to ask me about Mom’s six trips to rehab and why my home life was so screwed up, or how I’d wound up in jail, but she didn’t ask those questions like the other fourteen adults who’d interviewed me. Instead she leaned forward and rested her chin on her upturned palm.

“Story, what are your dreams?”

I took a deep breath and sat up straighter. I was ready for this one. “I’ve been thinking about some different career paths and weighing my options. I’m a voracious reader but I also enjoy mathematics, specifically algebra. So, I could see myself becoming a journalist or an engineer.”

She nodded. “Those are excellent career choices.” She paused and asked, “What are you passionate about?”

My face dropped into a frown and I looked away. I’d thought of every question I could imagine, but I never thought about passion. Of course I knew what the word meant, but it wasn’t like I had time to paint, or sculpt or write. Surviving filled my day planner. I glanced at her razor-sharp gaze. She was watching me stumble around the answer. I shook my head. “I… I don’t know.”

She set down the iPad and stylus and crossed her arms. She looked shocked. “You can’t answer the question?”

I tried to hide my anger. I should’ve seen this coming and planned an answer, even if it was a lie.

“It’s a dumb question,” I spat.

“I’m disappointed.”

I glared at her. “Disappointed? What were you expecting? Some kind of a show? Maybe I’d start reciting the Declaration of Independence for you?” I glanced at Jill but she was focused on her viewfinder. “Or was I supposed to just kiss your ass and act grateful that you asked to talk to me. Is that why you’re disappointed or did I miss something?”

She stuck her iPad and stylus in the messenger bag next to her. I sat back and closed my eyes. I’d screwed up and missed my chance, a chance I’d spent weeks planning for. I thought about what I’d just said. It wasn’t me. It was my mom talking. Even jail couldn’t keep us apart. I sunk lower in the chair and buried my face in my hands.

“Can I go back now?”

“Do you mean back to the unit or back to the street?”

“Both.”

“Absolutely. Ms. Sutton gave you too much credit. I’ll need to tell her she’s losing her touch.”

My head shot up. Ms. Sutton was the best teacher I’d ever known. Every day I was struck by the irony: I had to go to jail to get a great teacher. “What does she have to do with this?”

“Who do you think recommended you for the SPOT?”

SPOT was the Student Potential Opportunity Test and was given to kids in jail who proved they were literate and had more than street smarts. I’d heard stories about kids who’d aced the SPOT and left Lakeview. I’d seen proof that at least one had gone to college. Maybe it was mostly smoke, but when I heard it, I figured out a way to get arrested.

I stared at Margaret. I knew what she was doing. She was judging Ms. Sutton based on my behavior. If I didn’t do well in this interview, Ms. Sutton would probably lose a bonus or a promotion. That’s how adults worked. They were the cruelest to each other. Normally I wouldn’t care but Ms. Sutton was different from all the other adults I knew. I inhaled, visualizing the oxygen tingling my brain and suffocating the image of my mother.

“Your question is irrelevant.”

Her eyes darted toward Jill so I looked over at Jill too. Her finger rested on the on/off button but she hadn’t pushed it and the green light remained. Margaret was waiting to see what Jill wanted to do—and not the other way around. Something was weird.

“Who’s running this show?” I asked.

They looked surprised. Neither said anything and my nervous leg bounced like crazy. I was in real trouble now. I’d figured out their game.

Jill stepped away from the camera. “You’re very perceptive, Story.” She slid into the chair between Margaret and me and asked, “Why do you suppose I would allow Margaret to ask you the questions?”

I thought about my earlier conversation with Jill. Middlemarch. The fact that Margaret was supposedly late. “You wanted to watch me answer questions, but you also wanted to talk to me before we started. I wasn’t as nervous then.”

“Exactly,” she said.

Margaret and Jill exchanged a nod. Margaret stepped behind the camera and Jill leaned on the table. “Now, let’s go back. Tell me why having dreams is irrelevant.”

How could I explain? “Have you been to WalMart?”

“Once or twice, but I usually try to avoid it. I’m not much for obnoxious crowds.”

“Me neither, but it’s where you shop if you don’t have much money.”

“What does that have to do with your dreams?”

“So one day I turned into the baby aisle by accident and these three women were there. They came from the other direction so I could see their faces. The oldest was probably in her fifties. She’s holding a can of off-brand baby food and lecturing the youngest one, who’s a little older than me. She’s got on these teeny shorts and a string tank top. She’s pretending to listen, but she’s getting tired of standing there. She shifts her weight from one foot to the other and slides this toddler from her right hip to her left. I guess that it’s a grandma and granddaughter. Grandma’s talking about how it’s her disability check, and there’s no way she’s paying eighty cents more for the name brand. Every time she takes a breath, the granddaughter tries to tell her the name brand’s better for the kid because it’s organic. They’re getting louder and louder. Pretty soon the kid’s crying. The girl lifts her shirt and shoves him to her breast to shut him up so they can keep fighting.”

“What about the third woman?”

“She’s the one I noticed the most. I’m guessing she was the granddaughter’s mom.”

“Four generations,” Jill murmured.

“Yeah. She was leaning on the cart, not even paying attention to their fight over her head. She was there but she wasn’t there. She was checked out. It was the look on her face that I remember.”

“What did you see?”

“At first I thought she might be stoned, but there was a moment when the grandma said something really cruel and the mom closed her eyes, like she was trying to keep it together and not scream at her own mother.”

Jill moved so close to me that I could smell the mint on her breath. “And what do you think that look meant?”

“She’s helpless. Like she’d realized this was her life. The grandma ranted, and the granddaughter was too young to know that her life was going be about fighting over eighty cents, day after day, week after week and year after year. She didn’t see it yet but the mom got it. She was completely stuck and she’d made sure her daughter was stuck too. I think she felt bad.” Jill and Margaret exchanged a glance, but I couldn’t tell if they were happy or upset with my answer.

“What happened next?” Jill asked.

“I went three rows over and saw another grandma, mom, and daughter, only this daughter had two kids. So when you ask me about my dreams, that’s what I see.”

“You think that will be you.”

“Won’t it?”

“Where’d you get such an advanced vocabulary? Your teachers in school?”

I snorted, picturing tubby Mr. Gurlach behind his desk with a wad of chew in his cheek. “No, it wasn’t my teachers. When I was little and lived with Gran, she’d read the classics to me and we always had a word of the day. By the time I was in third grade, I knew a ton of words and the teachers kept sending me to the library during reading time. They didn’t know what to do with me. I just kept checking out books from the library.” Something occurred to me and I looked at Jill quizzically. “I don’t get it.”

“Get what?”

“My grandma did a great job with me but my mom’s a mess. How come she didn’t do such a great job with her?”

Jill glanced at Margaret again. It was like a private joke I didn’t understand. I hoped I wasn’t the joke. I thought I’d said something really stupid until she clutched my hand. I nearly jumped at her touch.

“Story, you’re amazing. I can’t explain why your grandma did better by you than your mother, but the fact that you even recognize the significance is incredible. That’s one reason why you’re special. That’s why we’re having this conversation. I want you to have dreams. I want you to achieve them. What if I told you I could make sure you never have to worry about eighty cents ever again?”

For a moment I didn’t breath. My plan had worked! “You could really do that?” I asked.

Her green eyes grew darker and she smiled like she was proud of me. “Story, that’s exactly what I’m going to do.”